Impact Investing: A Matter of Measure

The Ivey Business Review is a student publication conceived, designed and managed by Honors Business Administration students at the Ivey Business School.

A History of Sustainable Investing

In 2015, the United Nations released 17 Sustainable Development Goals aimed at helping countries solve pressing issues including poverty, inequality, and climate change. These goals focus on integrating economic development, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability into future development plans. While the goals offer a valuable, codified directive for governments and businesses, they ultimately reflect universally accepted ideas: people and corporations have a responsibility to look after the most vulnerable and protect our environment.

Ralph Nader’s 1965 exposé Unsafe at Any Speed tapped into a new wave of public concern about businesses that do not act in the public good. More recently, concerns about market economies’ abilities to protect society’s most vulnerable have been exacerbated by an increasingly globalized and knowledge-based economy which has left unskilled workers behind, while a lopsided recovery from the financial crisis has also called into question the fairness of financial markets. In fact, the share of the population with “little or no confidence” in businesses has risen from 26 per cent in 1979 to 39 per cent today.

As a result, consumers are more concerned than ever, demanding socially responsible behaviour from corporations. In the coming decades, this trend will accelerate as socially-conscious millennials inherit wealth from their baby-boomer parents.

Recognizing changing consumer preferences throughout the twentieth century, businesses understood that they needed to look beyond financial performance for their decision making and that they also had to consider their social and environmental impacts to avoid alienating customers. This was manifested in the rise of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the entrenchment of CSR as a ubiquitous term in strategy literature.

This change in corporate culture coincided with a new set of investing principles, resulting in the rise of Socially Responsible Investing (SRI). SRI involves evaluating investment opportunities not only based on their expected financial return, but also on their ability to promote ethical and sustainable business practices. Sustainable investing has grown rapidly as investors now consider environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors across $12 trillion of professionally managed assets, a 38-per-cent increase since 2016.

While consumers responded well to CSR initiatives and sustainable investing practices, they have remained skeptical about the true intentions of corporations and investors, as demonstrated by the increasing mistrust of the private sector. Consumers are often concerned that CSR initiatives are considered a marketing expense for companies while doing little to align the underlying incentives of the core business with socially desirable outcomes.

In response to some of these concerns, there has been a marked shift from CSR initiatives to a model focused on sustainably aligning incentives: Creating Shared Value (CSV). Whereas CSR initiatives are treated as cost centres, CSV argues that a company’s competitiveness and its community’s health are mutually dependent, implying that business decisions which create shared value are a profit centre.

One can think of the difference between CSR and CSV as the difference between Chevrolet announcing a new treeplanting initiative to offset its cars’ environmental impact—a cost centre to improve brand palatability—and Chevrolet announcing the production of the all-electric Volt: a profit centre which directly aligns the incentives of consumers and Chevrolet. While the introduction of CSR initiatives was mirrored by the growth of sustainable investing practices, the mainstream integration of CSV is likely to coincide with a new funding model: impact investing.

An Overview of Impact Investing

Impact investing is the process of investing in companies, organizations or funds to generate social or environmental impact in addition to financial returns. This can include investments in initiatives such as affordable housing projects, renewable energy companies, and health care clinics. While SRI also accounts for the ESG impacts of an investment, its ultimate goal is to minimize the financial risks posed by ESG concerns. Impact investing, by contrast, intentionally and purposefully seeks to achieve a positive social outcome from the investment. Moreover, impact investing measures and incorporates this impact into the risk-return profile of an investment while SRI does not. Consequently, impact investors may make concessions on financial returns if the social impact outweighs the decreased return proportionately.

Moreover, the fact that impact investments can often be entirely uncorrelated with the market makes them extremely attractive. For instance, the payout of Goldman Sachs’ recent Social Impact Bond in Utah—focusing on improving pre-kindergarten education to reduce reliance on special education—was dependent on the students’ academic success. Even impact investments with market exposure appear to perform on par or better than traditional investments, as evidenced by a recent metaanalysis of 2,000 studies on sustainable investing.

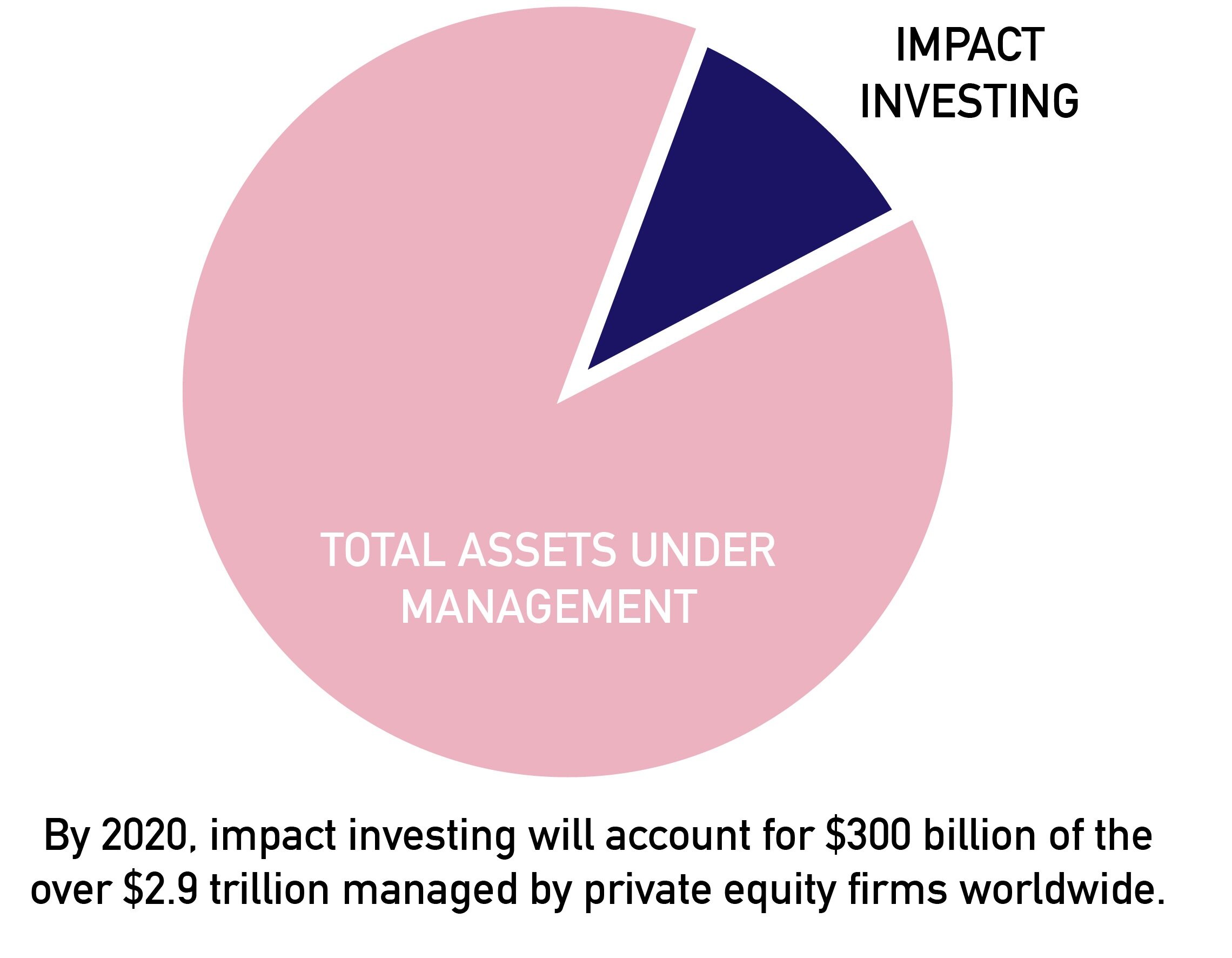

The total funds allocated toward impact investments are expected to reach $300 billion worldwide by 2020. Furthermore, a report surveying 82 asset management organizations showed an average growth rate of 13 per cent per annum from 2013 to 2018 in their impact investing assets under management. Firms such as BlackRock, Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs, and JPMorgan Chase have also included impact products in their portfolios.

Problems Affecting Impact Investing

Despite growing interest from major business publications, research firms, and institutional investors, coverage of impact investing still eludes mainstream media and financial curriculums. Often mistaken for SRI products, ESG investing, and microfinancing, the lack of widespread knowledge in impact investing has stunted growth. This is compounded by the lack of advisor knowledge. Consequently, awareness and accessibility remain issues as many investors are unaware of the investment vehicles available.

Many of the challenges affecting impact investing stem from the difficulty of standardizing impact measurements, which reduces the usability and reliability of impact return metrics. Consider an educational enterprise seeking to improve the knowledge and skills of a community with the ultimate goal of helping the residents escape poverty. Ideally, a return metric would be outcome-based—it would track the community’s improved skills. Instead, the only available information would typically be efficiency-based, such as total enrollment.

Ultimately, the majority of current metrics do not take into account the relative efficacy of an investment’s strategy, but instead only report on the investment’s performance and ability to execute. Even if such metrics were readily available, there would be substantial costs for data collection and analysis, the metrics would not be widely understood, and the technological infrastructure would not exist to include the metrics in standard data aggregators or analysis tools.

Finally, the lack of a standardized external auditing and control apparatus introduces additional accountability issues. Typically, impact measurements are self-selected, and unlike reports on a company’s financial performance, impact assessments are not subject to strict regulations by dedicated governmental bodies or mandatory thirdparty audits. Moreover, because the metrics used in these assessments are self-reported, they may not capture the actual impact of the investment. Imagine an affordable housing project which successfully provides many lowincome families with housing, but also causes a collapse in housing prices, diminishing the wealth of the rest of the community. It is likely that the firm would not consider such externalities in its reporting, thus overstating the project’s positive social impact.

Innovators in the Space

While there are significant challenges in the impact investing space, there are numerous innovators aiming to solve the problems limiting the sector’s growth. One such example is OpenImpact, which attempts to improve the accessibility of impact investments to investors by compiling key information for dozens of investment opportunities in an easily searchable manner. The website allows investors to screen using filters such as Sustainable Development Goal alignment, geographical region, and investor eligibility. OpenImpact also links investors to the websites of the businesses and funds represented on the platform. Although OpenImpact relays limited quantifiable information on the actual social impact of different funds, the website represents a step forward in allowing the average investor to allocate capital to the impact space.

Currently, OpenImpact uses a measurement taxonomy named IRIS 4.0 to categorize investment funds based on social and environmental impact objectives and target demographics. IRIS aims to create a standardized approach to measure the total financial and social returns of a variety of enterprises. Companies can individually measure their desired impact using IRIS metrics categorized by sector, beneficiary, operational impact, and financials. For instance, a company working to improve literacy rates could use the “Student Transition Rate” metric, which measures the percentage of students advancing to the next grade level, as a factor in measuring impact. Funds then use these measurements in reports to investors to benchmark the performance of an investment against the desired social impact.

While IRIS represents a significant step forward in the standardization of metrics for comparability between investment assets, its 559 metrics are limited in measuring efficacy rather than efficiency. For example, despite the existence of the “Full-Time Employees: Total” metric that measures the number of individuals hired by the organization, there exists no metric in the framework to measure the resultant increase in economic activity generated by the increased employment.

Impact investing analytics firms such as B Analytics are also aiding in the development of the market. B Analytics markets a software platform that allows investors to easily store and collect impact data from its portfolio. The firm uses the collected data to generate benchmarks so users can compare their investment to other sustainable businesses, impact funds, and traditional investments. The company also advertises that the platform can generate reports with analytics and visualizations to improve the users’ investments. Although the software suite offered by B Analytics is not yet as advanced as those offered for SRI or traditional investors, the company’s efforts in modernizing data collection and analytics in the impact investing space have the potential to truly help impact funds be more successful.

While many innovators have made tremendous strides in bringing awareness to the space and improving accessibility through aggregating investment opportunities, several issues remain that pose a threat to the growth and credibility of the space: the difficulties of measuring the “impact” of impact investing, improving accessibility for investors with different risk-return objectives, and integrating impact assessments into mainstream finance and investing platforms.

NGO Partnerships

Social impact innovators would benefit from the establishment of a strict auditing regime built on cross-sector partnerships to capitalize on a rise in social engagement and greater demand for impact assessment. Several NGOs and other non-profits are already working to address some of society’s largest problems. As an example, OpenImpact could develop partnerships with these NGOs, using them as objective auditors to measure the social impact of investments in that NGO’s realm of expertise. This would add credibility to the impact investing space, as OpenImpact could pre-screen companies and require them to agree to a quarterly impact audit, akin to public company financial reporting requirements, as a prerequisite to being listed on the platform. By adopting these processes and reporting requirements, OpenImpact can give investors the necessary information to make better decisions whileovercoming some of IRIS’s limitations.

As part of such an arrangement, OpenImpact could finance these audits through a revenue-sharing agreement in which a percentage of each investment sourced through its platform would be shared with the auditor. This would provide these third-parties with predictable and sustainable funding, thereby reducing their reliance on external fundraising, increasing their objectivity, and allowing them to focus on their own organizations.

Furthermore, OpenImpact could augment its impact assessment capabilities by using information technology to collect real-time data and implement track-your-impact (TYI) initiatives. For example, a prospective investor and investee could agree on key performance indicators prior to an investment, and the investor could require a consistent flow of relevant data to ensure sufficient efforts are being made to meet the indicators. In practice, TYI initiatives can be used to replicate the venture capital model of funding. If an impact entrepreneur is looking to finance his or her idea, but interested investors are reluctant to provide a large lump-sum payment, they can offer seed funding along with conditional follow-on capital subject to the venture meeting agreed-upon objectives. This would allow different types of investors to participate in different “rounds” of funding, better matching investors with their appetite for risk and increasing the volume of impact investment funding.

Taking Impact Investing Mainstream

As the adoption of nuanced, efficacious metrics for impact measurement increases, the dissemination of this data will be crucial in advancing the mainstream adoption of impact investing. Common investing platforms including Capital IQ, Bloomberg, and FactSet have shown an interest in the implementation of ESG metrics from external platforms including Sustainalytics and MSCI to service investors practicing SRI. Moving forward, the proliferation of impact-focused measurements from similar platforms like B Analytics and data from OpenImpact’s mandated audits will be essential in improving visibility and comparability for impact investing.

The power of impact investing lies in its ability to leverage the efficiency of capital markets while simultaneously aligning incentives to capture the positive intentions of traditional philanthropy. In doing so, impact investing is the best funding model to facilitate the mainstream introduction of CSV into corporate business models. However, failure to make improvements in measurement, accessibility across investor risk profiles, and integration into investing platforms will prevent impact investing from maturing. Strong support for accountability in impact measurement and the distribution of the resultant collected data will enable the industry to finally achieve mainstream visibility.