Seeing Green with Psychedelics

By: Mark Fortino & Rachel Rothstein

The Ivey Business Review is a student publication conceived, designed and managed by Honors Business Administration students at the Ivey Business School.

Content Warning: This article includes discussion of serious mental health issues and suicide, which may be triggering or traumatizing to some readers.

A Trip to the Psychedelic Market

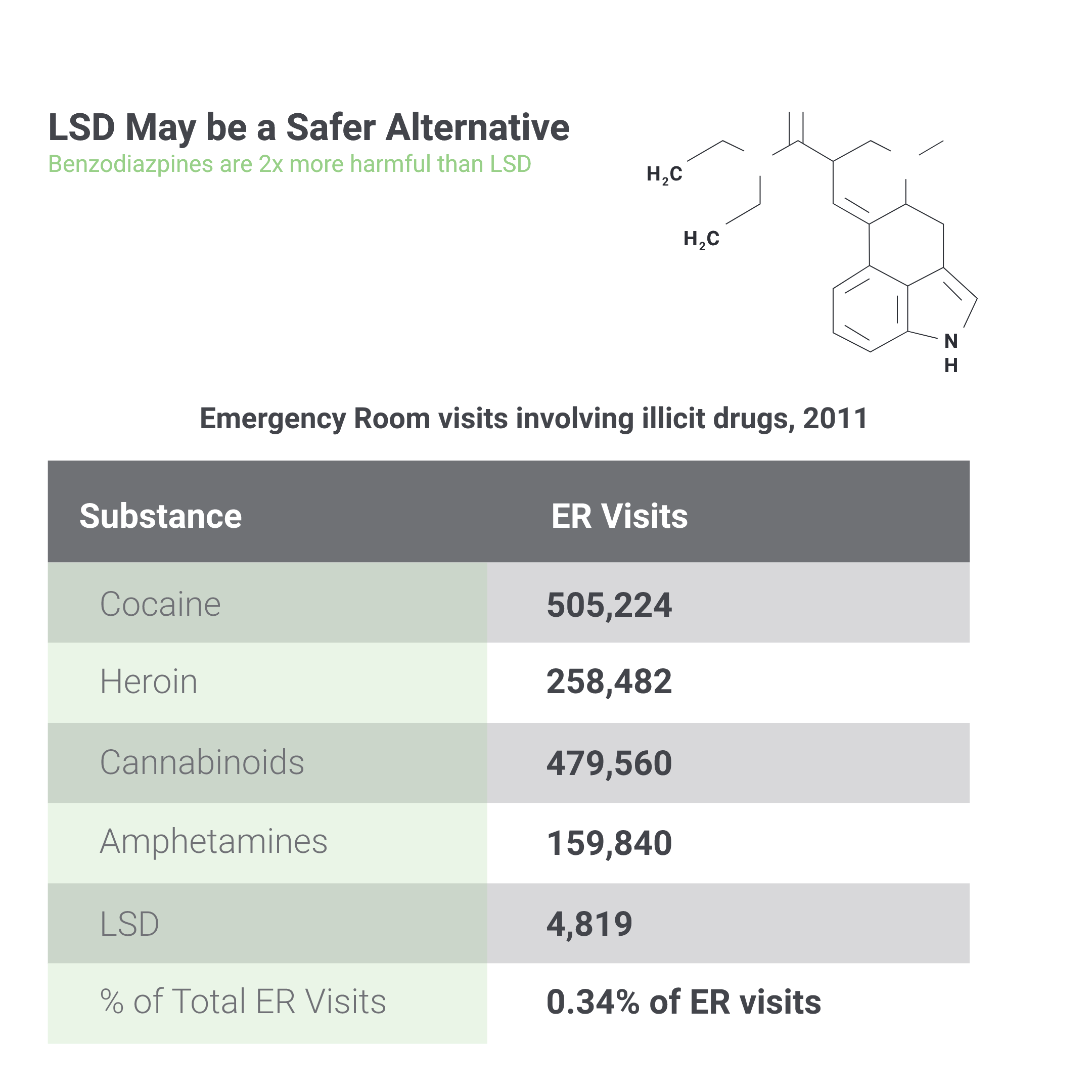

Despite being a relatively new establishment, the antidepressant market has experienced many innovations and controversies. The earliest treatments for mental illness relied on institutionalization, which was criticized for its unregulated and underfunded quality of care. By the mid-20th century, however, the introduction of antipsychotic drugs had brought significant changes. By 1977, a class of psychoactive drugs called benzodiazepines became the most widely-consumed medication worldwide for mental disorders. However, benzodiazepines presented harmful side effects, most notably addiction and withdrawal. This led to the development of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a new class of antidepressants, which had a reduced risk of addiction. Since the shift to SSRIs, the antidepressant drug market has grown 400 percent from the early 1990s to the late 2000s.

Today, despite the widespread usage of SSRIs and similar counterparts, the effectiveness of these mental health treatments remains a point of controversy. SSRIs have been criticized for their detrimental side effects during the initial stages of treatment, which can include panic attacks and suicidal tendencies, among other symptoms. Although they are marketed as non-addictive, patients can exhibit withdrawal symptoms. Experts have yet to find a clear answer to the efficacy of SSRIs as a treatment for mental illness, and this is further highlighted when examining relapse rates—the deterioration in mental health after treatment is completed. Relapse rates start at 40 percent for a patient’s first prescribed medication and increase by approximately 10 percent each time the patient switches antidepressants.

Big Pharma has Mush Room for Growth

Minimal innovation has occurred in the antidepressant drug market since the introduction of SSRIs. While Prozac and Xanax were extremely profitable for Eli Lilly and Pfizer in the 1990s when they were under patent protection, excess profits have since been eroded by generic drugs. With the influx of competitor products, antidepressants now comprise only a small portion of the largest pharmaceutical companies’ revenue. For example, Xanax and Zoloft made up only one percent of Pfizer’s total revenue in 2019, and Trintellix made up only 2.1 percent of Takeda’s total revenue in 2020.

The pharmaceutical business model partially depends on “product-hopping”: making minor tweaks to existing drugs before their patent expires as a method of maintaining protection. In the case of psychiatric drugs, companies have exhausted potential improvements significant enough to warrant FDA approval. While antidepressants are still profitable, companies have been reluctant to invest in completely new forms of treatment over more profitable areas such as oncology or diabetes. This represents a case of the Innovator’s Dilemma, where the incumbent pharmaceutical company avoids the risk of an invention that is a radical departure from what is currently considered adequate. As such, the number of psychopharmacological drug research programmes in larger drug firms has shrunk by 70 percent in the past decade.

Sporing Big through Innovation

The pervasiveness of mental illness and the lack of adequate treatments present a significant business and public health opportunity. The global markets for anxiety, addiction, and antidepressant medication sit at $4.5 billion, $42 billion, and $4 billion, respectively, with the antidepressant market expected to grow at a CAGR of 7.4 percent through 2023. Prozac’s success while it was under patent protection also served as an indicator of the market’s potential. In 1990, Prozac generated nearly $1 billion in sales, close to 22 percent of Eli Lilly’s total revenue. Despite a recent lack of innovation, these markets offer significant potential for both profitability and improvement of public health.

Getting Psyched for Psychedelics

Psychedelics refers to a class of psychoactive drugs that can put users under a state of altered perception, such as dream-like states or states with heightened senses. The most well-studied psychedelic drug compounds include MDMA, LSD, ketamine, and psilocybin—the key active ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms. Psychedelic usage became a symbol for the counterculture movement in the 1960s, eventually leading the FDA to ban the manufacturing and sale of all types of psychedelic drugs due to their limited “accepted medical use,” and high “potential for abuse.” Stringent regulation stalled development in the psychedelics market in the latter half of the 20th century.

Clinical research studies of psychedelics resurfaced in the 2000s as specialists continued to investigate their use as a mental health treatment. This new wave also led to increasing support from the FDA, which began to designate “Breakthrough Status” to MDMA and psilocybin, denoting their high potential for treatment and enabling acceleration of research trials. 2019 represented a pivotal year for clinical applications of psychedelics in which research on psychedelic drugs was reignited by the establishment of the Johns Hopkins Psychedelic Research Center. In March of that year, the FDA approved the usage of a psychedelic drug for the first time—esketamine, an intranasal antidepressant, was approved to address treatment-resistant depression.

A Non-Fungible Treatment

The major difference between psychedelics and SSRIs lies in their impact on brain chemistry and their treatment application. Psychedelics function generally by targeting areas of the brain to create a temporary chemical imbalance. By impacting connectivity within the brain, users can experience shifts of consciousness. Unlike antidepressants, psychedelics function instantly, and studies suggest that the effects of psychedelics could last for long periods after the drug leaves the patient’s system.

Compared to the traditional “pill-a-day” consumption method used for antidepressants, psychedelic-assisted therapy treatment may only be required monthly or annually, pending results from future clinical trials. Industry analysts estimate the drugs will be priced based on the current standard of care, incorporating differences in usage frequencies between traditional drugs and psychedelics. For example, LSD for anti-anxiety purposes will be priced assuming monthly or annual treatment based on daily prices for Cymbalta.

Studies on the effectiveness of psychedelics have shown favourable results. A 2014 John Hopkins study reports that the abstinence rate for previous smoking addicts was a remarkable 80 percent after six months of treatment with psilocybin. In a following 2015 study, participants with cancer-related depression or anxiety also reported increased mental well-being six months after a similar dose of the drug. Similarly, the use of MDMA therapeutics on patients with severe PTSD who were considered “treatment-resistant” obtained spectacular results, with approximately 70 percent of patients no longer qualifying for the diagnosis after 12 months, and the remainder having less intense symptoms.

Navigating Legal Truffles

Psychedelics are monitored by Health Canada under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, which limits its sale, import, and production. However, in the U.S., decriminalization and legalization laws vary drastically from state to state. Oregon became the first state to legalize psilocybin in 2020, and the Oregon Health Authority stated that this could provide a framework for assisted psilocybin therapy to be administered as early as 2023.

State legislation, however, is different from FDA approval, which would be required for medical use. Currently, psychedelic drugs are in the process of FDA approval for specific medical purposes across the entirety of the United States. Once clinical trials prove a psychedelic substance is effective for medical conditions, the FDA’s Controlled Substance team will make a new recommendation to the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) on how to regulate the substance.

Mycelling the Product

A positive psychedelic experience requires a safe and undisturbed setting, a calm mindset, and a supervisor. In practice, this would involve licensed therapists accompanying the patient throughout four to six hours of treatment with psilocybin, and even longer with LSD. In the subsequent hours to days following the psychedelic experience, therapists would guide patients through an integration period to incorporate insights into the individual’s life. Dr. Will Siu, a psychiatrist at MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies), suggests that up to 90 percent of the long-term benefits of psychedelics can occur during this integration phase. A study from MAPS claims that cost savings per patient to healthcare providers over a 30-year treatment horizon would be $103,200.

Seeing Green in Psychedelics

Psychedelic-assisted therapy represents an opportunity to relieve a growing mental health crisis while also tapping into lucrative profit opportunities. Pharmaceutical players looking to enter the space should consider forming partnerships with leading pure-play psychedelic companies and assist them in R&D to proceed through FDA approval. Such partnerships may act as a springboard, as pharmaceutical companies can acquire the right to the proprietary compounds and continue to develop them in-house. A similar strategy of using M&A to de-risk the process of in-house R&D was common at Allergan under the leadership of Brett Saunders. These partnerships could take one of several forms: development collaboration, an R&D reimbursement agreement, a full drug sale, or a licensing deal.

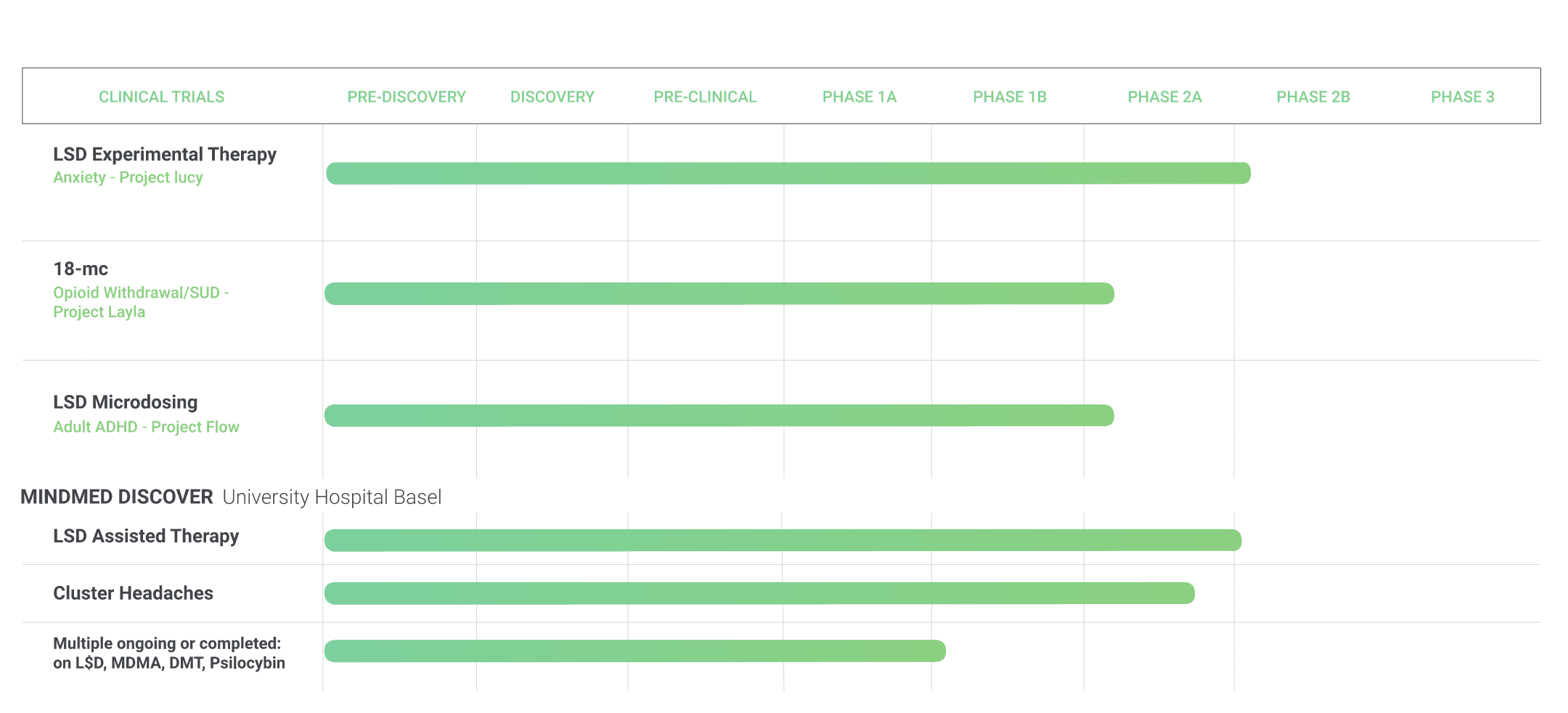

While many of the leading psychedelic companies such as Compass Pathways, Champignon Brands, and Field Trip Health would be valuable acquisition targets, MindMed is an optimal target for a major pharmaceutical company. MindMed is a leading psychedelic biotech firm, with a pipeline of three active psychedelic clinical programs in the development stage. As of Q3 2020, MindMed had $18 million in cash, which is expected to last until between Q1 and Q2 2021. At that point, it will need to raise additional equity capital, or receive funding from a strategic partner.

MindMed’s LSD anxiety treatment, Project Lucy, is currently in late phase two of FDA approval. The optimal time to partner for a large pharma player would be at the end of phase two and the beginning of phase three. At this point, human proof of concept data will have been recorded, which indicates low risk. Phase three is also the most expensive stage, with over 70 percent of total R&D costs taking place after this point. A partnership would give MindMed access to R&D expertise and an established commercial infrastructure for distribution and manufacturing purposes.

The Mushroom Moat

As academic support for psychedelics as a mental health treatment option grows, large pharma players have a timely opportunity to enter this emerging market. Through M&A activity and strategic partnerships, pharmaceutical companies can help smaller startups bring these products to life while reaping significant financial rewards. Among its peers, MindMed stands out as a particularly attractive potential partner given its anxiety treatment drug Project Lucy. A strategic partnership with Big Pharma could act as a foundation for future business for one of MindMed’s other drugs, such as 18-MC for opioid addiction treatment (with a $2.0 to $3.8 billion annual global market size), or LSD microdosing for ADHD (with a $9.1 billion annual global market size). Above all, the psychedelic space is surrounded by an economic moat, and with capital and expertise, Big Pharma could reap the benefits.