Interview: Hubert T. Lacroix

The Ivey Business Review is a student publication conceived, designed and managed by Honors Business Administration students at the Ivey Business School.

Hubert T. Lacroix, Chief Executive Officer of CBC

Hubert Lacroix is the current CEO of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and has been with the company since 2008 (re-appointed to serve a second term in 2012). Prior to CBC, Lacroix was a Canadian lawyer and a senior adviser with law firm Strikeman Elliot LLP – he was also an associate professor in the Faculty of Law at Montreal University where he teaches securities and M&A. Lacroix received a Bachelor of Law degree from McGill University (Montreal) in 1976 – he was subsequently admitted to the Quebec bar in 1977.

About CBC

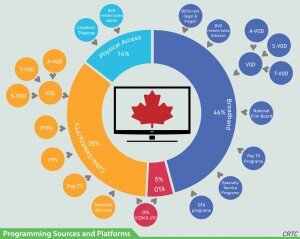

CBC/Radio-Canada is Canada’s national public broadcaster. Through the delivery of a comprehensive range of radio, television, internet, and satellite-based services, CBC/Radio-Canada brings diverse regional and cultural perspectives into the daily lives of Canadians in English, French and eight Aboriginal languages. CBC/ Radio-Canada also provides international reporting from a uniquely Canadian perspective, with foreign bureaus in places like Jerusalem, Washington and Beijing. CBC/Radio-Canada’s mandate is set out in the 1991 Broadcasting Act. CBC/Radio-Canada is accountable to all Canadians, reporting annually to Parliament through the Minister of Canadian Heritage.

IBR: Thanks for agreeing to take the time to speak with us. Perhaps the best place to start is with a question around ‘digital’. You have mentioned many times that the shift from the old ways of consuming content to the new, digitally-enabled ways is the biggest challenge faced by the CBC. What did you mean by that?

HL: The shift I am referring to is both in terms of how Canadians consume content and what content they’re consuming. In television in particular, what we are seeing is that the old, linear model of giving consumers pre- determined content at fixed times is going away. The new model – particularly for young people, but true to an extent for everyone – is all about greater flexibility: consuming on-the-go and in bite-sized chunks.

Naturally, this has an impact on the types of content consumers want as well. If there is one thing that’s clear, it’s that we cannot simply take, for example, a piece of news we broadcasted last night on The National and stick it on our website or mobile app and expect it to do as good a job at reaching Canadians. Everything has to be faster, shorter, and more hard-hitting on these newer platforms. This changes the skill sets we need, all the way from editorial and creative down to more technical skills.

The challenge is that despite the scale of these changes in digital consumption, many of the old ways of consuming content still remain strong today. It is true that they’re not growing the way digital is, but the average Canadian today still sits down in a chair and watches 28 hours of linear programming every week. That’s a lot of hours, and it means we have a large market to continue to serve even while we retool towards the new methods.

IBR: Your experience doesn’t sound dissimilar from some examples we have seen in other industries, such as financial institutions, which are dealing with explosive growth in digital while still needing to maintain and serve their core business. How is the CBC managing to serve both at once?

HL: Truth be told, it’s not easy, and it’s in fact made more complicated by the financial challenges we face. We are not able – as some have – to start entirely from the ground up and build a separate, digital-first organization with all of the new tools and technologies to serve this market. We started down that path in 2010 after I gave our leaders the challenge of spending 5% of their budgets on digital, but ultimately found it ineffective to have individual ‘labs’ separate from the core of our business. Not only did it have the potential to forge a cultural divide within the CBC between the new and old, but starting fresh also required a level of investment that we simply couldn’t sustain. Ultimately, we had to make this transformation happen within the structure we have today.

IBR: Are there other decisions regarding the digital transition that you are forced to make with the funding constraint?

HL: In general, I think it has required us to be much more deliberate and early with our bets in digital. We know that if we wait too long, we won’t necessarily have the resources at our disposal to play catch-up. We need to be first more often than most and if you look at where we are today, I think you would say that we are there.

At the same time, our constraints mean that we have to be much more targeted and focused in where we place our bets. We are always on the look-out for what the next game-changing platform will be, but we can’t chase opportunity where we’re not certain it exists. Instagram, Snapchat, and a host of other apps are growing and vibrant platforms. Could we do something through those mediums? Sure. But will they likely ever become core parts of our digital strategy? We don’t see it, and so we don’t invest in quite the same way.

Ultimately, given our financial situation, the key is to stay nimble enough that if something comes along to change the game, we can pounce.

IBR: Do you see these financial challenges ever resolving themselves? The federal government recently announced an additional $150M in funding, but more broadly speaking, what tools are at your disposal to ensure the financial sustainability of the CBC in the long term?

HL: It’s important to think about this question in terms of our three sources of funds. The first is the government contribution, which – notwithstanding the additional $150M you mentioned – is unlikely to grow significantly over time. It will also always be a volatile source, making it a difficult one to plan around in the long term.

The second is advertising. We have been squeezed in this regard as rates have fallen in the media industry, but we are making good progress in digital. One of the big advantages that digital channels possess is that unlike cable – where the broadcasters stand between us and the customer – we have much more direct access to consumer data. This lets us do much more from an advertising and targeting perspective, even if we are still learning how to make sense of all the new information.

The third is licensing of our content. Unlike most media companies, this is a small portion of our revenue. This is driven almost exclusively by our deal with Rogers for Hockey Night in Canada. Otherwise, the current regulatory regime doesn’t allow us to charge televisions service providers for our content, no matter how vital it is to any of their cable packages.

From my view, at some point this has to change. It is unheard of for a large broadcaster to operate this way. Even amongst public broadcasters it need not be the default model – I look at the BBC as an example, where viewers pay for access to the content.

No doubt some would question why we should receive both a subsidy and payment for our content. That said, I would counter with two crucial points. First, the major cable companies are the ones truly benefiting from the existing arrangement as they get the additional content for free. They should be the ones to pay. Given the competitive environment, I wouldn’t necessarily expect that cost to be passed on to consumers. Second, our mandate as a public broadcaster requires us to produce content that by its nature is unlikely to break-even from a financial perspective. The subsidy is the only way to make it economical to produce, but without compensation for that content it severely limits what we can do. The CBC model for producing television will die if we don’t adjust this structure.

IBR: This latter point on your mandate is particularly interesting, especially as we know there are divergent views. From our understanding, public broadcasting took root as a way of creating an informed populace in an era of dramatically increasing democratic participation. Now, universal suffrage is no longer novel and information is ubiquitous through the Internet. In your view, has that diluted the importance or changed the mandate of public broadcasters at all?

HL: Changed, yes, but diminished, no. The issue is no longer about access to information but rather curation and interpretation. With so many content options and the prevalence of social media, our society suffers from information overload more than anything. What is needed now more than ever, is someone to be trusted to make sense of it all. This is where we come in with a strong, non-partisan perspective.

Our mandate has morphed in other ways as well. The need to have a presence on digital – to ensure we are everywhere that viewers are – is the obvious one. Another would be though our focus as part of our 2020 strategy on local news. It’s a segment that’s vitally important to people, but has suffered badly from the decline in advertising and consolidation of classifieds online. As a result, small papers are closing and the private broadcasters are pulling back. This is where we put that government funding to good use – the content itself may not be profitable, but it’s important to show people that we have not abandoned them.

IBR: In the case of local news, however, wouldn’t it be fair to argue that some of this has been replaced by the prevalence of social media? Most of our connections on a platform like Facebook are local even if the platform itself is global in nature. If local news is of interest to us because it impacts the people we care about, wouldn’t social media be the ultimate curator in this regard?

HL: True, social media has its part to play, but the credibility concern is arguably more important on social media than anywhere else. There’s no control on the content and no filter on what’s important or even accurate. Yes, it may add relevance, but it in no way ensures accuracy or quality, which is extremely important. Take the attacks in Paris as an example; in the immediate aftermath, social media spread confusion as to the true nature of the attacks. Only until media organizations were able to filter through the noise were we able to create an accurate depiction of what was going on. That’s where I think our brand becomes paramount.

IBR: Beyond simply delivering a high quality product, how do you build this credibility?

HL: There are many ways. We are fortunate to have a long legacy of quality journalism behind us that makes our lives easier in the present day. A key piece though is putting our talented people front and centre. You know, generations ago Walter Cronkite was the most trusted man in America.

IBR: Much as Brian Williams was until recently…

HL: That’s right. They were there with viewers for all the big moments and, through adhering to the highest standards of professional integrity, [he] was the one they wanted to hear from the most when they needed the truth. We strive for that. Peter [Mansbridge] has that reputation. Adrienne [Arsenault] has that reputation. Scores of others of our journalists and personalities do as well. It’s a core part of our strategy to elevate the brands of these people. Making them recognizable, trusted faces that viewers can establish a ‘personal attachment’ to is a key factor in the success of what we do.

The challenge is that these personal brands are unlike any other asset we possess. As much as we want to help cultivate them, we must be careful to avoid putting constraints on what our people say and do. We have a clear code of ethics that all employees must follow at all times, but otherwise we must allow room for dissent and different opinions.

IBR: With all these challenges and changes, did you ever imagine yourself still sitting here when you took the job in 2008?

HL: No, I did not; in fact, I wasn’t even sure I wanted to take the job! The economy was in a tough position at the time and I was worried about the level of political interference. In time, it became obvious that there was a clear mandate to get the job done. I took it and don’t regret a moment.

Another key moment for me personally came in 2012. Shortly after I agreed to a second term with the CBC, we were faced with another significant cut in our funding. I knew at that point that the coming years would be painful at times and faced a choice about whether to stay. Ultimately, I knew it was my duty to see things through, not only to quell the fear that “the ship was sinking” but because I truly believe in our mission. The future still holds many questions but I know we are making a difference to Canadians, and for as long as I can, I want to continue to do so.