A New Crop of Investments

By: Max Jaychuk & Nick Xiang

The Ivey Business Review is a student publication conceived, designed and managed by Honors Business Administration students at the Ivey Business School.

The private equity (PE) landscape is looking for new, long-term growth opportunities. PE mega-fund managers such as Carlyle, KKR, and Blackstone now need to compete with their investors such as sovereign wealth funds, state-owned enterprises, pension plans, and large family offices which have become direct investors in the space. While investor appetite has remained high, there has been a buildup of dry powder globally for PE firms due to a shortage of traditional investment opportunities. Global dry-powder reached $1.2T at the end of 2014, an amount not seen since the buyout boom leading up to the financial crisis. The oversupply of capital in the buyout space has pushed up median purchase price EBITDA multiples from 7.8x in 2009, to 11.5x in 2014, the highest it has been in the past fifteen years. This expansion in acquisition multiples has dampened returns from investments in traditional private equity.

Another trend in the PE space is increased investor risk aversion. This has led to PE firms being pressured by fund managers and investors towards putting capital in high performing assets with a longer hold period than the traditional 3-5 years, along with charging lower fees. The pressure from investors to find quality assets at a low valuation and a longer-term hold has led mega-fund PE firms to shift away from traditional PE to more general asset management, including infrastructure and real estate.

Surveying the Landscape

One asset class that has remains underinvested is agriculture. In recent years, it has gotten increased attention with the number of private equity food and agriculture funds rising to 47 in 2014, up from only three in 2005. Many opportunities still exist for a PE player looking to diversify its asset mix away from LBOs. Agriculture is an asset characterized by long-term holds, with ample global opportunities and both positive demand and supply fundamentals, which will drive land values. Specifically, farmland provides many benefits. By owning a real asset it increases the safety of principal and gives both income and capital appreciation to owners. Farmland also possesses attractive risk-return characteristics such as returns uncorrelated with traditional investment classes. Additionally, its low cyclicality provides high value retention during recessions. While land prices and weather patterns vary, over the long-term farmland has provided strong returns and is underpinned by growing demand for its production and limited supply of productive arable land. These characteristics align with the fact that the PE industry has been seeking a more stable, reliable income stream compared to other traditional LBO candidates, such as industrial, healthcare, or consumer retail companies. Historically, farmland has been ignored by PE firms as an asset class due to a highly fragmented market, restrictive ownership rules, and its unsuitability to short term hold periods; however, these barriers are decreasing.

Furthermore, the macroeconomic environment will be positive for agriculture over the long-term. The steady growth of the world’s population and rising meat consumption, particularly in developing nations, will require a 50% increase in food production by 2050. In addition, after years of crop yield improvements meeting the increases in demand, the yield improvement curve is flattening. Yields are no longer improving on 24-39% of the world’s most important cropland areas. The global average projected crop yields are lower than the required 2.4% per year rate of yield gains needed to meet food demand by 2050, necessitating an alternative solution. This presents an opportunity for asset-hungry investors.

Planting the Seeds

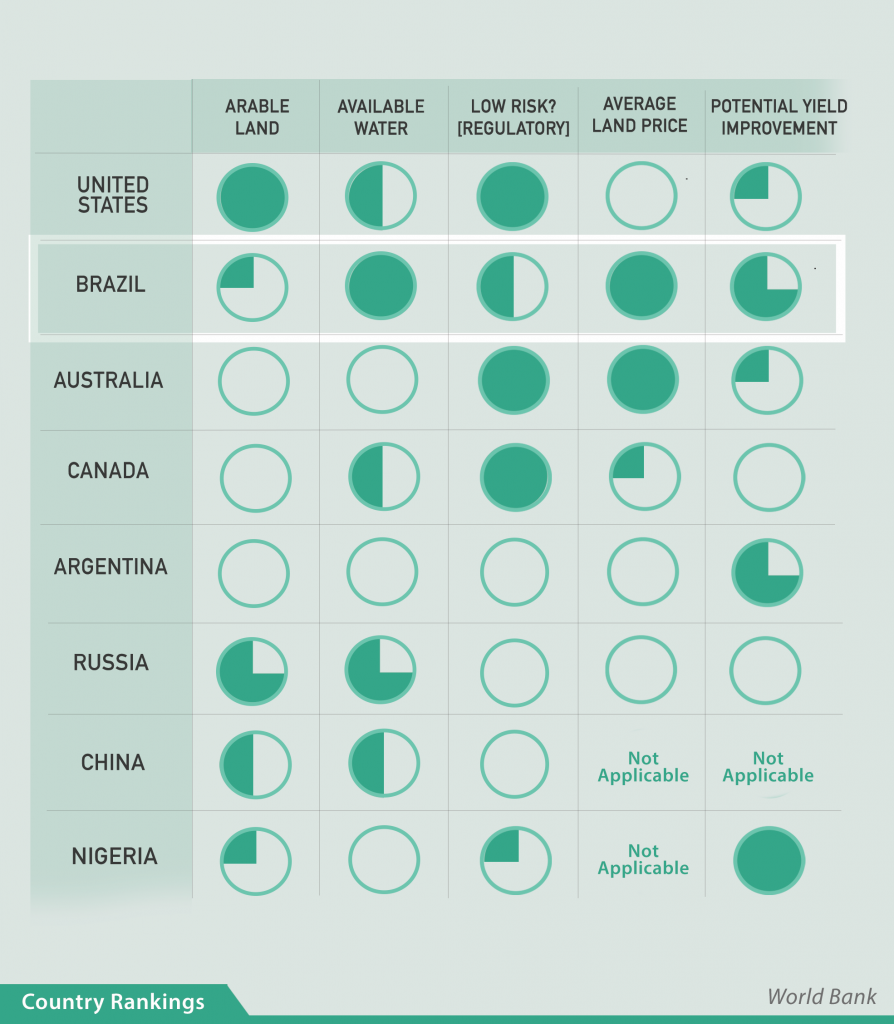

While farmland investing presents attractive characteristics, the potential for stable returns varies significantly across geographies. Climatic conditions, land prices, corruption, and land rights are of utmost importance. North American and European farmlands have presented stable returns to investors over the past 20 years, although these markets are relatively saturated, with high land prices relative to productivity. In contrast, South America remains a relatively undeveloped market with some of the most ideal climatic conditions, suitable for growing crops year around, and has the world’s greatest water resources. Brazil, in particular, presents an interesting opportunity due to its relatively strong land ownership rights. Brazilian land receives high levels of rainfall, which makes it some of the world’s best farmland. These climatic conditions create a longer growing season that allows for two to three crop rotations per year, compared to North American farms, which are generally limited to one cycle per year.

Although Brazil has seen some farmland appreciation in recent years, agricultural land in many areas of Brazil remains reasonably priced on a productive basis. Brazil also has the added benefit of having ports that can satisfy the demand of African and Asian nations, which are projected to have the largest food supply gap in years to come. Brazil currently has 73M HAs of arable land, with potential for expansion of an additional approximately 100M HAs, 34.3% of the world’s total expansion potential. The crop yield for every dollar of land invested in Brazil is much higher (1.29 kg/$) than the US (0.67 kg/$). This, along with the fact that Brazil has a cereal crop yield that is only 65% of the US’ suggests there is the potential for agronomical improvements and yields converging closer to comparable productive land in the US. Brazil has one of the lowest ratios of cultivated land to suitable land (60%) and achieved yield to potential yield (40%), further proving that Brazilian farmland has potential productive upside.

Harvesting the Crop

Many PE funds have been trying to diversify into alternative asset classes; however some, such as Carlyle, have struggled to diversify despite success in the LBO space. To note, 85% of Carlyle’s annual net income came from PE, compared to Blackstone (32%) and Apollo (48%). To diversify its business, Carlyle has been funneling as much as $5B towards a longer-term fund with investment horizons as long as 20 years. This aligns with agriculture’s more long-term nature and illustrates why Carlyle could be well-positioned to invest in the agriculture industry. Relative to the other mega-funds, Carlyle has maintained a strong presence in South America since 2008, with two offices (Peru and Brazil) and over a dozen investment professionals. Although Brazil has been known to have provided some difficulty to foreign investors, Carlyle has had the experience of making several investments in the country over the past few years, demonstrating both its knowledge and willingness to invest in the space. Experience in the region provides Carlyle with an advantage over other large investment firms within Brazil’s unique business environment. Carlyle needs an entrance strategy that minimizes risk, while still providing returns in line with the firm’s expectations.

To implement this strategy, Carlyle would need to start a new fund, as the existing fund’s footprint in South America focuses primarily on LBOs. As Carlyle’s current funds are sized between $150M-800M, an agriculture fund with approximately $400M of committed capital for the first fund would match Carlyle’s current strategy and is comparable in size to other agriculture funds that have invested in Brazil. The investment horizon would be longer than traditional PE, ranging from 10-15 years.

Agriculture investments can be approached through a landlord model, where farmers pay agreed rents to the investor. This model is low risk, providing investors with only 8-10% return. Alternatively, an operational model where the land owner would operate the land themselves can yield higher returns, but exposes investors to weather, commodity price, and operating risk. However, over the long-term, the effect of these risks could be decreased. The typical land operational strategy would involve purchasing the land, hiring external managers and farmers to manage the land, transforming the land, growing and harvesting the crops, and transporting the product to processors. Carlyle should implement the operational model to expand into Brazilian farmland.

Although Carlyle is known for taking an active investment strategy, the agriculture operational strategy would involve different skills than the typical LBO model that Carlyle issued to. As such, it must form a joint venture with SLC Agricola (SLC), the largest Brazilian local farm operator that has experience working with foreign investors. Carlyle would provide the necessary capital and own a 49% stake, in exchange of benefitting from the operational expertise and local market knowledge of SLC, who would own a 51% stake. This would also ensure Carlyle is meeting Brazil’s foreign ownership restrictions. SLC is publicly traded and was founded in 1977, making it a reputable partner that Carlyle could depend upon, minimizing the investment risk. The company’s business model is based on large-scale modern production systems and currently operates 16 farms across six Brazilian states, totaling 343,600 HAs, proving that it has the capacity to manage Carlyle’s farmland portfolio. SLC also has experience working with foreign investors, as it previously entered into similar partnerships with Valiance and Mitsui. The partnership would work as follows: Carlyle would provide the financing for purchasing the land, equipment, and working capital, while SLC would hire the farmers and use its internal operations team to develop and manage the farmland.

Calculating the Yield

Brazil has approximately 8.4 million sq. km of land, of which 33% is being used for agriculture and 8.7% is arable. Much of this land is Cerrado, or savannah land, which is available in large swaths and has the characteristics to become productive farmland. Carlyle should pursue a Cerrado transformation strategy with SLC in order to maximize returns. Transformation is the process of converting arable land into usable farmland. Capital expenditures for transformation range from 40-90% of the land cost, but will add significant value uplift. In addition, where possible, the partnership should work towards consolidating the Cerrado farmland. Economies of scale exist for farming; if Carlyle were to invest in multiple properties, it could consolidate and distribute farming equipment, decreasing operational expenses and boosting its IRR.

Other foreign investors have already proven this model can work logistically with the desired returns, although with limited capital. Valiance, a British asset management firm, launched a joint venture with SLC in 2012 to acquire Cerrado land and develop it into high-performing farmland. It estimated an IRR of 22% through this venture. Similarly, Brookfield Asset Management focused on land transformation through its $330M AgriLand Fund, which manages 220,000 HAs of land. Like Valiance, Brookfield estimates an IRR of 20-25%. These examples show that the desired return is feasible.

Carlyle should invest in Cerrado farmland in the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Goias. These farm areas have limited access to suitable infrastructure to transport products to ports, resulting in land prices of $1,000-2,000/ HA. These prices are significantly lower than the more saturated regions; top quality farmland in Brazil can be valued as high as $10,000/HA. The Brazilian Government has committed to developing additional transportation infrastructure in the next 10 years near these regions that would reduce transportation and export costs by up to half and have the potential to increase annual income yields by 4-5%. This could also translate into further land appreciation, resulting in a higher valuation upon exit. In order to further boost returns, Carlyle could also propose to the Brazilian government to complete a cash infusion into the infrastructure assets through the company’s Global Infrastructure Fund to accelerate construction.

Together, Carlyle and SLC should focus on the transformation and consolidation of large pieces of Cerrado land to maximize efficiency and generate attractive returns. Time is of the essence as the supply of Cerrado land will eventually be eliminated due to infrastructure improvements and increased investor capital. Success in Brazil may lead to Carlyle expanding its agriculture strategy to other parts of South America, globally positioning itself as a leader in the asset class before other PE firms get started.