Three’s Company, Four’s Allowed

By: Colin Lernell & Rajdeep Mukherjee

The Ivey Business Review is a student publication conceived, designed and managed by Honors Business Administration students at the Ivey Business School.

“I’ve never seen how a four-player [wireless] market can work in a country like Canada. I never thought of it as a sustainable model,” said Nadir Mohamed, CEO of Rogers Communications, in a July press conference. In the face of unrelenting regulators with the political will to introduce a “fourth wireless player in every region of the country,” Mr. Mohamed and Rogers’ incoming CEO, Guy Laurence, might consider never saying “never”. Instead, the two CEOs need only look to France for an example of how they might actually be able to capitalize on the situation.

The largest of France’s “Big Three” wireless operators, Orange (formerly France Telecom), helped new entrant Free Mobile simultaneously grab market share, hurt competitors’ margins, quelled consumer and regulatory tempers, and even earned significant revenue on the entrant’s growth. With Canadian regulators likely to set roaming rates and push for foreign entrants to ensure a fourth player’s success, Rogers might need to reconsider its own deterrence strategy when dealing with Canadian entrant, Wind.

Vive La Liberté

Prior to 2011, in a scenario eerily familiar to Canadians, France’s telecommunications industry was in a state of distress in the minds of its wireless consumers. The French Big Three telecoms held nearly 90% of the market, were charging high prices, and were sharing a suppressive strategy to stifle new entrants. A dissatisfied public pushed French regulators to facilitate the entry of a fourth wireless operator.

Enter Free Mobile in 2012. Igniting 10% to 50% cuts in competitors’ rates, Free Mobile took 11% market share in under two years. Free was able to accomplish this after signing an exclusive wholesale network-sharing deal with Orange to cover 97% of the French market. Orange, the largest operator in France, with roughly the same market share that Rogers holds in Canada at 37.5%, is estimated to have earned more than €2 billion on the Free deal, while still experiencing 3.2% year-over-year subscriber growth through 2013. On the other hand, the second and third largest operators, SFR and Bouygues Telecom (BT), lost 2% market share each, slashing margins and losing revenue, without recovering a cent. Rogers might be concerned with short-term market share, but the Orange deal demonstrates the strategic advantage of being a facilitator.

Rogers Has the Most to Lose

In the event of a foreign or domestic entrant gaining traction, Rogers has the most to lose of the Big Three in the current environment. Rogers is the largest wireless operator in Canada with 34% market share, compared to 28% each for Bell and TELUS. Rogers has a strong presence in Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia; the provinces where new entrants such as Wind are looking to expand. Rogers also received 57% of its revenues and 64% of its operating profits from the wireless segment in 2012; compared to 30% and 53% of revenues for Bell and TELUS respectively. Furthermore, Bell and TELUS benefit from a shared network infrastructure, having built out their tower networks together, reducing each other’s capital expenditures while capitalizing on economies of scale.

Push or Pull?

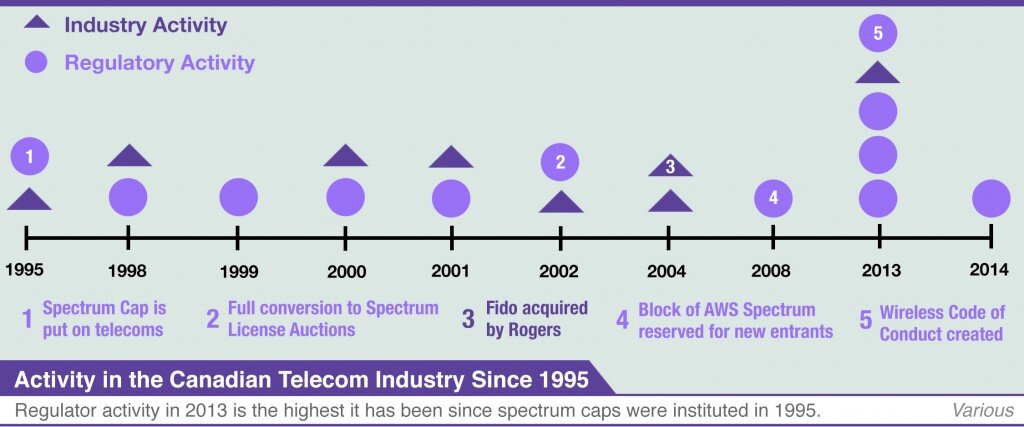

Rogers can either continue deterring Wind and other entrants’ growth or facilitate their inevitable presence. Historically, despite political and regulatory push-back, the big three effectively kept new entrants below a collective 5% market share. This remained effective until regulators redoubled their efforts in the hopes of spurring competition, courting large foreign competitors, regulating mobile contracts and fees, and striking down most Big Three bids to reconsolidate the market.

Deterring New Entrants

Rogers, Bell, and TELUS have sought to keep entrants small: they have lobbied the government to prevent pro-entrant regulation, inhibited negotiations on tower and network-sharing deals, and successfully used stand-alone sub-brands such as Chatr, Virgin, Fido and Koodo to compete on price without reducing the parent-brands’ margins. Continuing this strategy would have three consequences:

Regulatory Vendetta

First, dissatisfied consumers will continue to push for regulation to bridge any competitive advantage Rogers, Bell, and TELUS have over Wind and other small players. This occurred through 2012 and 2013 when the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) created a new “Wireless Code of Conduct,” which reduced contract lengths, enforced phone unlocking, and limited termination fees to increase churn between firms. With international roaming caps and investigations underway, regulators show no signs of slowing down.

Let Them Roam

Second, the CRTC has forced Rogers to negotiate a domestic roaming deal with Wind and other entrants; the CRTC would be pressed to set those rates themselves if they remain high. Roaming agreements currently do not allow Wind to offer its users 3G-compatible network coverage or unlimited roaming offerings like those of the Big Three.

French regulators threatened rate-setting until Free’s launch, while the United States Federal Communications Commission went ahead with U.S. rate-setting in 2008. Regulators in Canada have already begun the pricing of fixed-line broadband internet reselling, and will likely enforce network-sharing prices between Wind and all-incumbent networks if nothing changes.

Stranger at the Door

Third, Canadian regulators have prevented foreign ownership of telecom companies for national security and protectionist reasons. Regulators recently amended this policy to allow for foreign entrants to own companies with up to 10% market share due to their concerns that the failure of small players would lead to low-cost sub-brands closing their doors, and a subsequent increase in prices. Although a foreign investor would not be able to own over 47% of a telecom with greater than 10% market share, having a small player with 2% market share would be an attractive investment opportunity, especially with Canadian regulators actively courting foreign telecoms. This would provide favorable regulation in exchange for competition.

Regulators have already prevented the indirect equity owner of Wind from purchasing Allstream, citing national security concerns. Having a competitive domestic fourth player would likely reinforce this conservative approach to foreign investment.

The worst case for Rogers would be the entrance of a large foreign player. United States telecom giant Verizon Wireless reportedly considered entering the Canadian market by acquiring Wind in the summer of 2013. Although Verizon backed off, it has kept an ear to the Canadian market by having lobbyists on the ground. With more capital for marketing and infrastructure expenditure, not to mention considerable brand awareness, a firm like Verizon could turn a small player into a serious contender in the Canadian market.

Keep Your Enemies Closer

Rogers should reserve resources spent on deterring Wind, and instead facilitate its growth to create monetary value. The market share captured by a foreign entrant such as Verizon would dwarf that of Wind’s organic growth. If an exclusive network-sharing deal is negotiated instead, it could pre-empt CRTC-regulated roaming rates. This would allow Rogers to retain sole revenues from Wind users roaming on its networks instead of splitting revenues with Bell and TELUS. Rogers could then calm regulators and politicians who would be able to claim a win in their efforts to increase competition.

Profiting on Wind’s Growth

If Rogers is to facilitate Wind’s capture of market share, it will have to incur losses. However, there are three reasons why Wind’s growth will not be as pronounced as Free Mobile’s. First, Canada’s population density is lower than France’s, reducing domestic roaming demand to 30% of the market. Second, unlike Free, Wind does not have a TV, phone, fixed-line broadband, and wireless bundle to attract bundle-discount subscribers from the Big Three. Third, Wind currently has poorly perceived network quality.

If Rogers facilitates Wind’s growth, it will see an initial decline in market share, but this will be temporary. Projections assume a 10% decline in Rogers’ average revenue per user (ARPU) with market growth based on analyst projections. Despite short-term losses, the long-term strategic benefits are significant with Bell and TELUS likely to amass similar losses without recovery. Simply aiding Wind’s growth, however, is not enough for Rogers to take full advantage of this opportunity.

Short-Term: Network-Sharing & Royalties

Rogers should negotiate and sign an exclusive network-sharing deal with Wind. This would be both a wholesale roaming deal and a deal to supplement coverage within Wind zones. Traffic can be selectively pushed between Rogers’ and Wind’s networks when necessary, with only Wind paying for the extra coverage. Such a deal is unlikely between Wind, Bell, and TELUS – the latter two already share a network, creating complicated negotiations and possible capacity issues.

Appended to that deal should be a royalty agreement. Since Wind could serve subscribers outside of Wind zones, Rogers should earn royalties on any Wind customer using primarily Rogers’ networks. This will benefit Wind as it can quickly gain market share and still reap the lifetime value of those customers as it builds out its own towers.

Long-Term: Tower-Building

Once a relationship has been established, Rogers should negotiate a tower-building deal with Wind in Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta. Rogers has already signed tower-building agreements with MTS in Manitoba and Videotron in Quebec in 2013 to split high capital costs, indicating that it sees merit in such deals. There are no obvious partners in these other provinces, while Bell and TELUS already have the competitive advantage of splitting costs on building, upgrading, and maintaining network infrastructure. Alberta in particular has the largest and fastest growing adoption rate of mobile devices, and newly-developed areas require significant investment.

Over 52%, or $1.1 billion of Rogers’ capital expenditures come from its wireless segment. Saving on wireless infrastructure expenditures means that Rogers can invest saved funds in its higher-growth segments, such as media, machine-to-machine, home monitoring, and its new financial technology ventures.

Facilitated Disruption

Incumbents in a deregulated environment normally use a deterrence strategy for disruptors. This often ends in unfavorable regulations and a loss of market position to entrants with favorable rules on their side. By switching to a facilitator strategy, Rogers would mitigate an aggressive regulatory environment, while saving on infrastructure costs, creating a stabilized long-term partnership with a competitor. This would level the playing field with its two nearest rivals. Mr. Mohamed may not have seen a sustainable four-player model yet, but perhaps he or Mr. Laurence can make one happen while reaping the rewards.